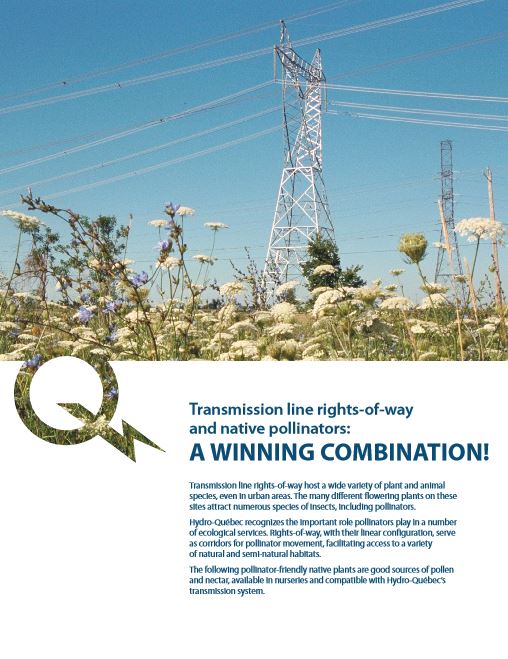

Background

Insects are a diverse group of animals that provide many ecosystem functions that support life on earth. However, despite their important roles, insects have often been shunned. Understanding how they live and being able to tell them apart can go a long way in feeling safer outside, enjoying the incredible biodiversity at our doorstep and wanting to help support these tiny allies.

Bees and their look-alikes (e.g., many wasps and flies) are important pollinators of wild and cultivated plants, including most flowering plants present in our gardens. Many insects, including solitary wasps, also keep other insect species in check by predating on them – an underestimated service for the well-being of our ecosystems. This service is now used more and more in agricultural settings to control insect pests and is of interest to scientists and industry alike.

When we think about bees and wasps, we usually picture the social species i.e. Honey Bees, bumble bees, yellow jacket wasps and hornets; and we learned to fear them because of their sting. However, these few species hide a real diversity in these insect groups of the order Hymenoptera (the group that includes ants, bees and wasps), including a lot of variation in morphology (their bodies’ form and structure) as well as lifestyles. Most importantly, most of these other species are not aggressive and usually do not sting (note: only females can sting!).

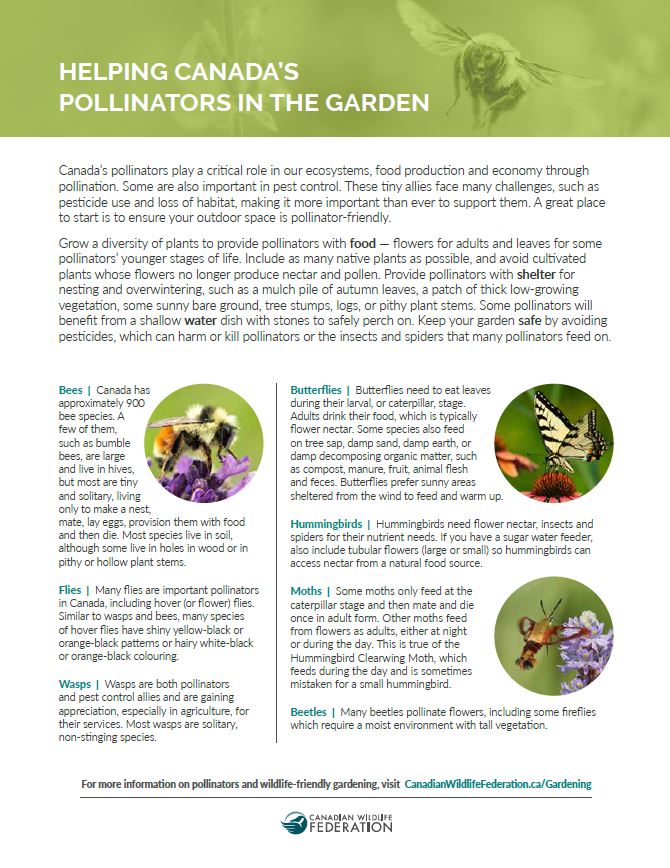

The group of bee and bee-like insects is large and telling them all apart confuses most of us. Bees alone account for more than 20,000 species worldwide and approximately 900 species in Canada! Some species are endemic, which means they can only be found in particular geographic regions. Moreover, some species are very specific in their needs and can only be found nesting in certain soil, for instance. Others can only be found living near a certain plant — they are called floral specialists. Other species are more “generalist” and can be found on many flower types in most regions.

© Kevin Burke

© Peter Soroye

Look-alikes

How to Tell the Differences between Bees, Wasps and Flies

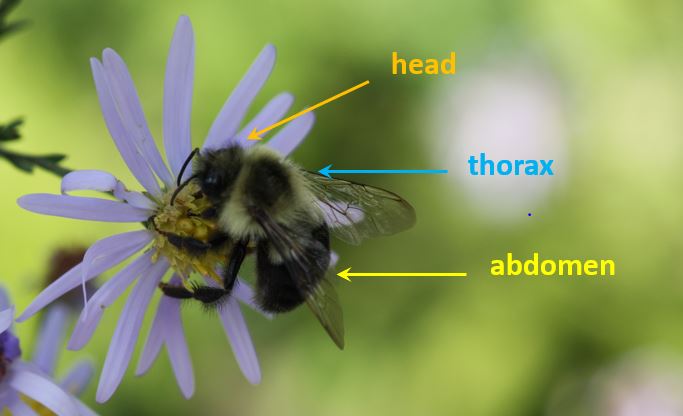

Bees and wasps are close relatives which explains why they look very similar. Bees often have hairs specially adapted to collect and carry pollen on their bodies, legs or abdomen. Wasps, on the other hand, are typically not as hairy as most do not collect pollen to feed their young. A group of bees called cuckoo bees, do not harvest pollen and instead “steal” the nest of other bees; those bees resemble wasps in their appearance which makes it much harder to differentiate the two groups for the untrained eye (at least for this group of bees).

Flies are not closely related to bees, but some flies have evolved to look like some bees and wasps to deceive a potential predator (in thinking they can sting). A major difference between bees and flies is the number of wings: bees have a total of four wings — although the second pair is usually hard to see, hidden under the first — whereas flies have only two wings. Moreover, bees tend to have longer antenna and smaller eyes, located on the side of the head compared to flies whose eyes face more at the front.

Bee on Buttonbush © Sarah Coulber | CWF

Fly on Buttonbush © Sarah Coulber | CWF

© Tovah Kashetsky

© Kevin Burke

Food Gathering

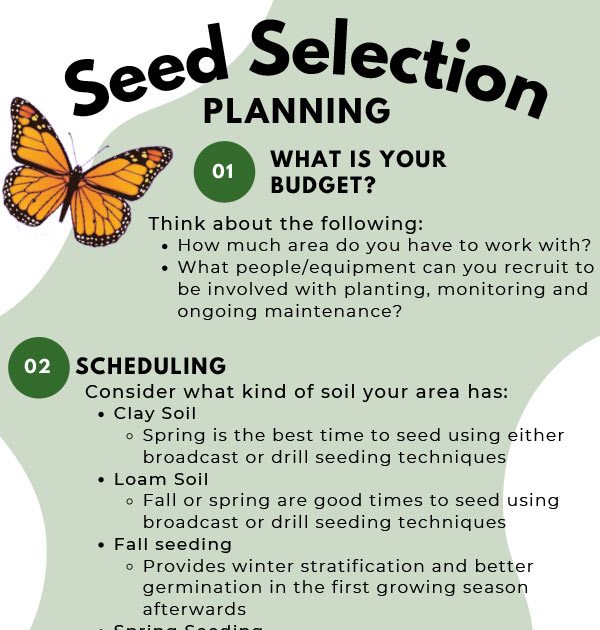

Most bees are known for gathering pollen and nectar as food resources. There are two main pollen-carrying specialized structures that allow them to bring this food to their young: the corbicula and the scopa, the latter having more variations in its location, shape and size.

Only Honey Bees and bumble bees have a corbicula, found on the hind tibia (which is the middle section of the leg). These bees gather pollen, mix it with nectar and then pack it for transportation. This corbicula is also known as a pollen basket or pollen sac. Some species of bumble bees do not have corbiculae as they are cuckoo species that lay their eggs in nests of other bumble bees, thereby not needing to provide their young with food.

Other pollen-collecting bees transport dry pollen on scopae. These are areas of specialized hairs growing densely on certain parts of the body. Depending on the type of bee, the scopa is typically either on the underside of the abdomen (as in the family Megachilidae), or on the hind legs. These specialized hairs can sometimes be lighter in colour (orange, yellow or creamy white) which make them stand out.

More rarely, some bees carry pollen internally by ingesting it and storing it in their crop (as the genus Hylaeus, the masked bees) which they can then regurgitate as provisions for their offspring.

All bees need pollen (as a protein source) and nectar (energetic fuel made of sugar) to grow to the adult developmental stage, where they then mostly consume nectar. Female solitary pollen-collecting bees pack their provisions in their nests in what is called a cell, a tiny chamber for their offspring to develop. Then, females lay an egg on top of the pollen ball before closing the cell. The egg then hatches and grows to be a larva which feeds on the food resources available within the cell.

Although bees seem to visit all flowers, they tend to have preferences in their diet (like us!). Some are generalists, meaning they have a wide-ranging diet when it comes to the flowers they will visit, while others are more specialised. The specialist bees collect pollen from a single plant family or from just a few plant genera. Some specialist bees though, are very specific and will gather pollen from only one particular plant genus or even a few plant species (as with squash bees). Diet specialisation allows bees to be well adapted to collect resources from these plants, but they could be more susceptible to environmental change and threatened by the negative effects of human activity.

The exception of cuckoo bees

Another group of bees mentioned previously, cuckoo bees (also called kleptoparasitic bees), have females that do not collect nor carry pollen but rather lay their eggs in the nests of other bees (the cuckoo female bees or their larvae eventually kill the other bee’s egg or larvae). They usually specialise on certain “host” bees and will only be looking for these hosts’ bees’ nests. You can spot them when they are hovering over the ground looking for underground nests or hovering near cavities, although this behaviour is also seen in the spring with queen bumble bees and other early nesting bees as they search for suitable sites to make or enter their nest. Cuckoo bees search for host nests and try to enter them when the female mother is out.

Life Cycles

- Of all the bees found in Canada, only the introduced Honey Bee, most of our bumble bees and some sweat bees are truly “eusocial”. This term refers to the most evolved form of sociability in insects (ants are also eusocial). Eusocial bees live in a colony in a single nest, with a reproductive division of labor (the female “workers” take care of the young, forage, clean or guard the nest, etc.) and the queen is the only mated female that lays eggs. The only responsibility of the queen, once the nest is established, is to produce young and different generations of offspring that will overlap.

Photo: Peter Soroye

- More than three-fourths of bees live a solitary life. Once these bees emerge from their nest, they mate and the female finds a nest site alone. Depending on their nesting needs, some female bees gather resources such as leaves, flower petals, mud or resin to line the nest walls. She then lays eggs in individual cells that she provisioned with food and seals the nest to protect it against the elements and predators. These females die soon after.

Of these solitary nesters, sometimes they will nest in aggregations in the ground where many individual nests can be found close together. This behaviour is thought to have some advantages like sharing the most suitable conditions for a nest site location and having multiple females defending the nests’ entrances against predators etc. Some bees are called communal as they share a tunnel entrance, but they show no structured division of labor and no other form of sociality.

Photo: Lydia Wong

Where They Live

- Most native bee species and wasps are called ground-nesters as they excavate a nest underground. They build a tunnel from which they create individual cells or other galleries to expand the nest. These bees tend to use a mixture of their saliva and a waxy secretion (from a gland near their abdomen called the Dufour’s gland) to line and waterproof their nests, protecting them from extreme weather conditions. These nests are very inconspicuous but can be spotted when a tumulus (a mound) is formed at the entrance, with a hole in the middle, indicating where the soil has been excavated from within. However, nests are closed most of the year while offspring develops.

Photo: Peter Soroye

- Other bees are called cavity-nesters. Some cavity-nesting bee species will nest in plant stems that are hollow or pithy and therefore soft enough for the female to chew through to form the nest and make a row of cells in the stem. This is an important reason to allow hollow stems of plants such as elderberry, raspberry, sumac and others to have old stems left on the plant, in particular if one end is open as it then has a good chance of nesting bees within it. Other species will nest in pre-existing cavities in wood holes, rock crevices, old insect nests, under tree bark and even in snail shells! Finally, some bees, called carpenter bees, will dig their own nest in wood (note: they still belong to the cavity-nesters’ category)!

Photo: Heather Holm

Honey Bee© Sarah Coulber | CWF

Challenges with a Managed Bee Industry

While we enjoy benefits of the managed bee industry, it does have negative impacts on our native pollinators that are important to be aware of.

One concern includes the domestication of our native bumble bees that are used specifically to pollinate greenhouse crops. The other is the competition Honey Bees pose with our native bees when they forage for food, as a single colony within a hive holds thousands of individuals that harvest pollen and nectar to feed themselves. This includes both farmed Honey Bees and those that leave, establish a new colony outside their home hive and become feral. These situations also have the potential to spread pathogens between domesticated and wild bees.

These are unintended impacts but they are impacts nonetheless. Some of our native bumble bees are now imperiled in part because of these effects and therefore there is a need for industry standards to be created in order to significantly reduce or eliminate these impacts.

Bee Families

In Canada, bees are divided in six families (the seventh family that exists worldwide is only present in Australia). Members of a family are grouped together by certain shared similarities. Families are broken down into smaller groups called genera (singular is genus) by more specifically shared characteristics. Some genera, like that containing bumble bees (Bombus), have several species in Canada while others have fewer. For a more detailed explanation, see the section “Understanding Scientific Names”.

Below is a list of all six bee families found in Canada with the most common genera detailed. This list is not complete, and you may encounter bees that do not fit into any of these genera. Even if some genera are easy to identify by sight (for example, Bombus), most bees are hard to distinguish from one another and experts usually need a microscope to tell species apart.

This information also includes nesting and feeding habits to help you plan or maintain your garden in the hopes you can support and/or at least minimize any harm that your actions may have. For more wildlife-friendly gardening information, visit our Gardening for Wildlife section.

© Lydia Wong

© Peter Soroye

Understanding Scientific Names

All plants and animals have names and we usually use their common names when talk about them. While this is helpful, the name itself tends to be different depending upon the location and languages. This is why scientists give all living things a scientific name, also called a Latin name or a species name. This scientific name is more precise and universally understood no matter where you are in the world or what language you speak.

The way scientists come up with names for things is by grouping them by their common traits. At a general level, plants are grouped together as are animals. Within the animal group, subgroups exist to differentiate mammals from insects from reptiles etc. There are many levels but the information here on these pages focuses on the more specific groupings of families and genera (singular genus). Within each genus are individual species. Each species has a scientific name that consists of two words: the genus and the “specific epithet” that identifies that particular plant or animal. Scientific names are always in Latin and written in italics, with the first letter of the genus in capital.

For instance, the Common Eastern Bumble Bee’s scientific name is Bombus impatiens. Bombus refers to the group of bumble bees and impatiens refers to that particular kind of bumble bee.

As to plants, the Rose Family has several genera including Rubus (with raspberries and blackberries), Prunus (with plums and cherries) and Amelanchier (serviceberries). Each of those genera have species like the Black Raspberry (Rubus occidentalis), Choke Cherry (Prunus virginiana) and Saskatoon Serviceberry (Amelanchier alnifolia).

Identifying Bees

To help you identify the bees you see in your garden or along a trail, take a photo or note as many characteristics as you can; its colours and their patterns, its size and the kind of plant the bee was on, if you know it. You can then post them to bumblebeewatch.org or iNaturalist.ca for assistance. Your photo might even help a scientist keep track of population changes in your area or find that a species is now in your area that wasn’t before. There is also a project you can participate in should you wish to share the wildlife you find in your garden: CWF’s Gardening for Wildlife iNaturalist page.

In the News

-

Product of Canada: The Wild Side of Our Home and Native Land

March 17, 2025, CWF Blog – When people think of Canada’s wildlife, moose, beavers, and loons usually take centre stage. But what about the species that only exist in Canada, the true “Products of Canada” in the natural world? These lesser-known plants and...

Papers & Handouts

Additional Resources

Sign Up for Timely

Articles and Tips

Special thanks to Cécile Antoine, PhD Candidate at the University of Ottawa for her tremendous help with this text.

SOURCES:

Holm (2017). Bees – an Identification and Native Plant Forage Guide

Holm (2014). Pollinators of Native Plants

Wilson and Carril (2016). The bees in your backyard. A guide to North America’s bees. Princeton University Press

Carril and Wilson (2021). Common bees of eastern North America. Princeton University Press

Ascher, J. S. and J. Pickering. 2021. Discover Life bee species guide and world checklist (Hymenoptera: Apoidea: Anthophila). http://www.discoverlife.org/mp/20q?guide=Apoidea_species