What is migration?

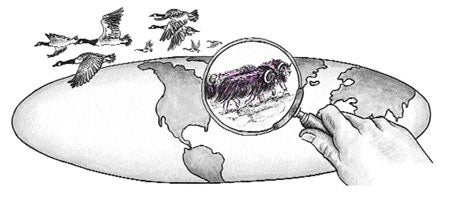

If you've ever watched the skies in fall, you've probably seen a huge, dotted V soaring overhead — a flock of geese migrating south. Geese aren't the only living things that make seasonal trips, sometimes thousands of kilometres long, from one place to another. Everywhere, from the Arctic to Antarctica, finned, furred, fanged, and feathered travellers are on the go.

Who does it?

Countless species of birds, mammals, reptiles, amphibians, fish, and invertebrates (spineless animals): woodland caribou by land; green darner dragonflies by air; northern bottlenosed whales by sea; yellow walleye upriver; speckled trout downstream; muskoxen uphill; bighorn sheep down dale; garter snakes out of hibernacula; bull frogs into marsh bottoms.

Why do they do it?

To stay alive. As seasons change, migrants must meet their basic survival needs in more than one place. They may go somewhere that is warmer or colder, has longer daylight, offers more to eat, or provides a safe haven to raise their young.

How do they know when to leave?

Shrinking food supplies, shifting winds, dwindling daylight, falling temperatures, or the start of a particular stage in life — such cues give migrants the instinctive urge to take flight, make tracks, or put to sea.

How do they know where to go?

Scientists believe migrants navigate by the position of the sun and stars, as well as by landmarks, such as mountains, rivers, and coasts, and climatic features like prevailing winds. Fish, especially salmon, "smell their way home" to the waters where they passed their early lives. Such insects as butterflies follow their noses using a well-honed chemical sense. A mysterious "sixth sense" may also help to keep migrants on track. Scientists have found traces of magnetite in pigeons and monarch butterflies. This magnetic material may act as a compass, enabling animals to navigate by sensing the Earth's magnetic fields.

What role does habitat play in migration?

All wildlife needs healthy habitat, that is, a place with suitable food, water, shelter, and space. Animals that migrate need several habitats. They may breed in one habitat in summer, spend the winter in another, and migrate along a corridor in spring and fall. A corridor is a chain of habitats for feeding and resting during a trip. It might include wetlands, wooded wind-breaks, sandy beaches, abandoned railway lines, or other habitats, depending on the species migrating. Since long-distance journeys demand much energy — in the case of birds, up to 12 times more than the amount usually required — migrants have to store up fuel as body fat before leaving, or else find abundant sources of food along the way.

Copyright Notice

© Canadian Wildlife Federation

All rights reserved. Web site content may be electronically copied or printed for classroom, personal and non-commercial use. All other users must receive written permission.