Start Right in Your Schoolyard

When we set out to create sustainable schoolyard habitats, it’s not always obvious where to begin. For example, Christ the King Elementary School in Whitehorse, Yukon, once faced the daunting task of transforming its barren asphalt schoolyard — a virtual parking lot — from grey to green.

From the beginning, the Kindergarten to Grade 6 students helped plan the removal of the asphalt and its replacement with native trees and shrubs, a grass and wildflower meadow, nesting boxes, a pond, and an outdoor classroom. Plans are now under way to re-establish a stand of lodgepole pines that existed on the site earlier this century.

What was described as an “inner-city nightmare” a few years ago is now a living example of the rapid strides we can make towards creating sustainable schoolyard habitats.

Plant Roots in the Future

Only a few hundred years ago, much of Canada was one enormous forest. Across the country, we've cut down trees for paper and timber or to clear the way for farms, cities, and highways. The most effective way to reverse this trend, while creating schoolyard habitat, is to plant trees. Years from now, your students might return to the schoolyard with their own children and list the amazing sustainability benefits of the roots they put down when they were young.

Trees provide a remarkable selection of food and shelter for countless wildlife species; enhance and beautify the landscape; cut down pollution by absorbing carbon dioxide and releasing clean air and water; prevent soil erosion caused by wind and water; buffer noise by absorbing and deflecting sound; and save energy spent on heating and air-conditioning by blocking winter winds and providing summer shade.

- Provide maximum sustainability benefits by choosing drought-resistant, native trees that supply both food and shelter. Conifers, such as eastern hemlock, white spruce, white pine, balsam fir, and red cedar, grow faster than deciduous trees, require less care, and provide year-round cover. On the other hand, the fruits, nuts, and seeds of deciduous trees, like red oak, black walnut, sugar maple, wild crab-apple, and Manitoba maple, provide substantially more food value. Small trees and shrubs (examples include staghorn-sumac, red-osier dogwood, hawthorn, red raspberry, choke-cherry, Saskatoon-berry, and common juniper) are much faster growing than larger trees and offer great food and shelter.

- Plan to arrange trees individually or in clumps, thickets, windbreaks, edges, and hedgerows. Consider planting the trees in a raised bed, surrounded by a retaining wall, if the soil in your schoolyard is of poor quality.

- Obtain native trees from nurseries, roadside ditches, a friendly landowner's woodlot, your district forester, or a local development site where the trees would otherwise perish. For best results, acquire trees at the large seedling or sapling stage (0.5 to 2 m tall).

- Store saplings in cool areas away from sun and wind. At this stage, their roots are very fragile and need special care. Soak them just before planting.

- Plant in the morning, evening, or on a rainy day — preferably in spring or fall, when trees are dormant.

- Dig a hole slightly deeper and wider than the root system. Place a bit of loose soil and a handful of bonemeal in the bottom of the hole.

- Put the sapling in the centre of the hole, with its roots just below ground level. Gently spread the roots and place soil around them until the hole is two-thirds full. Plant burlap wrapped roots as they are, after loosening the sacking from the trunk.

- Pour a pail of water into the hole, add the remaining soil, then gently tamp down the earth to remove air pockets. Leave a shallow bowl of earth around the trunk to collect water.

- Prevent competition with other plants for water, light, and nutrients by removing weeds from a 1-m radius around the trunk and applying a layer of mulch (organic material) about 5 cm deep.

- Water the tree regularly during the first summer, when it's most vulnerable to drought.

- If necessary, surround the sapling with wire mesh or a tree guard (a spiralling plastic sheath) to protect it from lawnmowers and small rodents.

Sow Seeds of Sustainability

A great way to jump-start the cycle towards ecological sustainability is to grow native plants, trees, and shrubs from seeds harvested in your area. They'll boost the benefits of other schoolyard planting projects by fostering the native floral heritage on which all wild species depend.

- Obtain permission to collect seeds from private or public lands, such as meadows, fence rows, or forest edges.

- Harvest seeds and fruits from mid-September to late October, favouring plants that attract birds, butterflies, and small mammals. Be sure to leave any threatened plant species undisturbed. Remember that it is unsafe to eat fruit without the approval of an expert.

- Collect 10 or 20 different types of seeds and fruits and store them in separate paper bags. (Consult a field guide to see that they come from native plants.) Label each of the bags with the date and location of harvest and the species' name.

- Never harvest more than 10 percent of a wild seed crop. Leave the rest to propagate the next generation of plants and to nourish such creatures as squirrels, foxes, and meadow voles.

- Remove seeds from fleshy fruits like mulberry, common elder, and highbush cranberry right away to keep them from rotting. Allow them to dry.

- Many seeds have to undergo natural processes before they can sprout. For example, scarification (the wearing away of the seed coats) occurs when fruit seeds pass through an animal's digestive tract. We can duplicate this process by scarring hard seed coats — rubbing them back and forth against sandpaper or nicking them with pliers. To scarify the seed coats of certain species like staghorn-sumac, bring water to a boil, immerse the seeds, remove the water from the heat source, and allow the seeds to steep overnight. Stratification — repeated freezing and thawing in winter — has to occur before the seeds of milkweed and many other native trees, shrubs, and wildflowers can sprout. To mimic the effects of stratification, place seeds in a plastic bag with wet sand or sphagnum moss. Then refrigerate them for two or three months.

- As a general rule, sow seeds to a depth of about twice their thickness by gently pressing them into the soil, then covering them. Very small seeds, such as those of grasses and goldenrod, need only be lightly scratched into the soil and tamped down. Water regularly until the plants are established.

- Get planting projects off to an early start by sowing some seeds in your classroom in late winter or early spring. Sow the seeds in flat planting containers, place them in a bright location, and keep the soil moist until seedlings sprout. Cardboard egg cartons make excellent planters. Being biodegradable, they provide a model of sustainable use — you can plant them right into the soil in late spring.

Turn a Fence into a Sustainable Feast

Transform a concrete jungle into a wildlife paradise! You don’t have to dig up every square metre of pavement to grow year- round sources of food for insects, birds, and small mammals. No matter how small your schoolyard may be, you can make the most of a tight squeeze by offering wildlife sustainable food sources in border areas. Any fenced boundary around your schoolyard, preferably in a sunny location, is great place to start.

- If your schoolyard is paved, start by digging up a 15-cm strip of asphalt along the fence row, filling in the excavated trench with earth.

- Plant an assortment of drought- and disease-resistant climbing vines along the base of the fence. Bittersweet, wild grape, Virginia creeper, and virgin's-bower will provide food and leafy cover for wildlife. Entice hummingbirds, honey-bees, and bumblebees by training scarlet runner bean and honeysuckle vines onto the fence.

- If more space is available, you can supply additional food and shelter by planting fruit- and nut-bearing shrubs and small trees alongside the vines. The following plants (many of which precede their fruit with showy flowers beneficial to bees and butterflies) are sustainable food sources par excellence:

- Canada plum, common elder, thimbleberry, sand-cherry, wild black currant, prickly gooseberry, raspberry, pin cherry, and Saskatoon-berry offer spring and summer fruit for a wide range of wildlife.

- Red-osier dogwood, American mountain ash, buffalo-berry, winterberry, and common choke-cherry provide fall food to help birds prepare for the frigid winter or the long migration south.

- Highbush cranberry, hawthorn, wild crabapple, white spruce, red cedar, snowberry, beaked hazelnut, common juniper, and staghorn-sumac supply vital nourishment that lasts through winter and early spring, when wild food is scarcest.

- Weed the fence row regularly, watering new vines, shrubs, and trees until they're well established.

Create a Sustainable Shelter for Songbirds

A tiny forest songbird called the prothonotary warbler is in deep trouble in southern Ontario. As few as four to 13 pairs of these endangered bright yellow birds remain in Canada. Like many other woodland birds, they are gradually disappearing as we carve up forests for logging, farming, roads, and human habitations. This “fragmentation” decreases the distance between a forest’s edge and its interior, making songbird nests more vulnerable to predators like cats, skunks, crows, and raccoons. At the same time, cavity-nesting birds (like the prothonotary warbler) are having a harder time finding shelter because of the decreasing availability of hollow trees.

But there is reason for hope. The eastern bluebird, too, was once a rarity. Its numbers plunged due to habitat loss and the invasion of the European starling, which usurps tree cavities and deprives native birds of nesting sites. Thanks to people putting up artificial nesting boxes throughout its range, the eastern bluebird has made an extraordinary comeback. The Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada recently removed the eastern bluebird from its list of species at risk.

We can help solve the songbird housing crisis — while practising a truly higher form of sustainability — by keeping our human junk out of landfills and turning it into songbird shelters. What's garbage to us can be home to birds!

Turn Scrap Wood into Bird Houses

Mount nesting boxes on posts or under eaves to shelter songbirds and boost their populations. This simple structure will accommodate bluebirds, prothonotary warblers, tree swallows, nuthatches, titmice, chickadees, and wrens, as well as deer mice and flying squirrels. Invasive starlings and house sparrows can be excluded by making the entrance hole no bigger than specified in the following instructions.

- Reduce waste and material costs by using scrap wood, which most lumber yards will sell at a tremendous discount or donate. Waste-exchange services in many Canadian municipalities also supply reusable lumber at nominal prices or free of charge.

- Start with a single plank of scrap pine or cedar, 3/4" x 5 1/2" x 4' (lumber is sold in imperial measures).

- Cut the plank into six panels: 11" (back), 8" (front), 8" (roof), 8" (side), 8" (side), and 4" (floor).

- Assemble panels using 2" coated flat-head screws. To keep the wood from splitting, pre-drill screw holes with a bit slightly smaller than the diameter of the screw.

- Drill a 1 1/8" diameter entrance hole 1" from the top of the front panel (1 1/2" diameter for bluebirds and tree swallows, 1 1/4" for nuthatches and flying squirrels).

- Drill four 1/4" diameter drainage holes in the bottom panel and two 1/4" ventilation holes near the top of each side panel.

- Mount the box 6 to 10' from the ground, no later than mid-April.

- Unscrew one side panel and clean out nesting materials each fall.

Transform schoolyard waste into brush piles

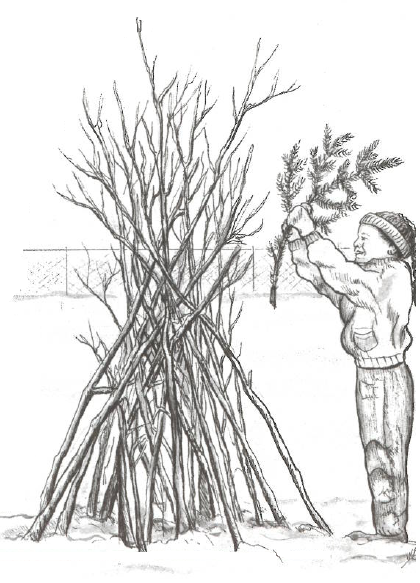

Recycle woody debris, such as fallen branches and clippings from pruned shrubs and trees, to create shelter for songbirds. Brush piles not only provide year-round cover for birds, they also are excellent nesting sites for small mammals and invertebrates.

- To build a brush pile with optimum value for birds, select eight or so straight, untrimmed branches about 2 m long.

- Arrange the branches in a teepee-like framework, with butt-ends anchored in the ground and tips interlocking. The idea is to create an internal space where occupants can perch safely off the ground.

- Pile evergreen boughs on the top and sides of this framework to form a dome.

- For added benefit, train climbing vines, such as Virginia creeper, scarlet runner bean, or honeysuckle, onto the brush pile during planting season.

- Each year, add a few new boughs. Leftover corn stalks will make a welcome addition to the brush pile in the fall.

Keep the Waterfowl Comeback on Track

North America's waterfowl population is making a remarkable recovery. After decades of decline due to drought and the loss of endless hectares of wetlands and grasslands under the farmer's plow, ducks are reappearing in eye-popping numbers — most notably throughout the Prairie pothole region. The small ponds and marshes that still dot the area are brimming not only with water but also with mallards, wigeons, gadwalls, and teal, thanks to extraordinary rainfall and a burgeoning movement to reclaim waterfowl habitat. Setting the trend towards more sustainable land-use practices are programs like the North American Waterfowl Management Plan, a campaign to rehabilitate waterfowl habitat in Canada, the United States, and Mexico.

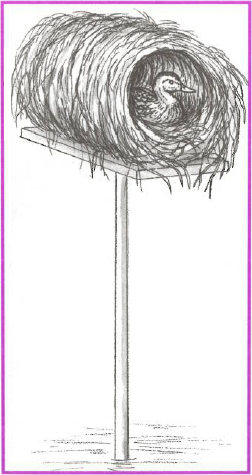

Now's your chance to "get quacking" and help keep the comeback on track by creating habitat where waterfowl can feed, breed, nest, and rest. Providing nesting cylinders has proven to be enormously successful with mallards, pintails, and teal in open wetland areas, such as the Prairie pothole region. The materials needed for this project are sold in imperial measures, so the following instructions use feet and inches.

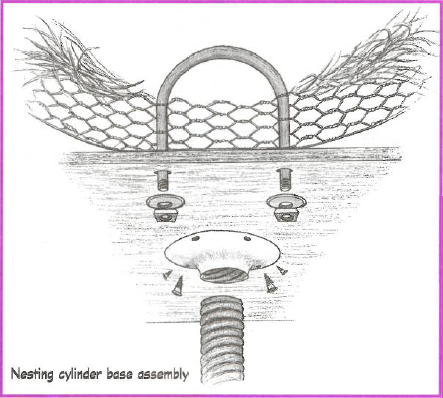

Start with a 3' x 7' length of chicken wire or galvanized stucco wire.

Start with a 3' x 7' length of chicken wire or galvanized stucco wire.- Roll the first 38" length of wire into a cylinder (approximately 1' in diameter) and fasten in place.

- Continue to roll the remaining 47' length of wire, lining the 1 1/2' space between the inner and outer layers with a generous amount of straw (preferably flax).

- Attach the cylinder to a 1" x 8" x 3" wooden board, using heavy wire or two 4" U-bolts.

- Screw a floor flange onto the bottom of the board. The final assembly (mounting the structure onto a support pole) takes place in the field.

- Choose a site in a marsh fringed by cattails and bulrushes, on the edge of open water 1' to 4' deep. The water should remain until at least mid-summer.

- Install the nesting cylinder by April 1, preferably in winter, when you can easily bore a hole through the ice to drive the support pole into place.

- Pound a 2" diameter galvanized support pole, approximately 6' to 8' long, at least 2' into the marsh bottom. The nesting cylinder should be at least 3' above the water's surface, so the required length of the pole will depend on the depth of the water. The pole should be threaded for easy connection to the floor flange at the bottom of the structure. Protect the threading by temporarily screwing a coupling onto the pole before driving it into the marsh bottom.

- Attach the structure by screwing the floor flange onto the support pole, positioning the nesting cylinder crosswind to prevent drafts from entering.

- Place additional straw in the cylinder, fluffed to enable the hen to arrange it.

- Check the structure for damage each spring and supply new nesting material.

Turn Tractor Tires into Toad Abodes

Amphibian numbers are plummeting in Canada. With their sensitive skins, amphibians are defenceless against acid rain, toxic chemicals, and ultraviolet rays increased by depletion of the Earth's ozone layer. Frogs, toads, and salamanders are also vulnerable to habitat fragmentation, as civilization drains and bulldozes wetlands for roads, houses, cottages, industries, and schools. As amphibians lose their habitat, many are forced to lay their eggs in rain-filled tire ruts and ditches, puddles, and water that collects in swimming pool covers. Countless tadpoles expire every year because they happen to hatch in the wrong place at the wrong time.

The booming b-r-r-rum of the bullfrog's love song and the leopard frog's guttural snore are less raucous than they once were, but you can help keep the chorus from croaking by creating amphibian habitat. You can easily turn an old tractor tire into a pond by removing one sidewall. Create a small wetland by building several of these ponds around a heavily planted site. At the same time, you'll be reusing some of the millions of tires that would otherwise end up in landfills every year.

- Choose a partially shaded spot near an unmown section of lawn.

- If you're using an old tractor tire, cut off one sidewall with a sharp knife or saw. Dig a hole 0.5 m deep, tapering down, and wide enough to accommodate the tire.

- Remove any stones and line the hole with a pool liner or discarded waterbed mattress.

- Place the tire on top of the liner. Cover the edges of the liner and tire with flat rocks.

- Cover the bottom of the pond with a 10-cm layer of gravel.

- Set rocks near the side of the pond at varying depths so toadlets can climb out.

- Fill the pond with tap water. Let it stand for at least a week, allowing the chlorine to dissipate before adding plants or animals.

- Submerge potted aquatic plants as egg-laying sites for toads, hiding places for tadpoles, and perches for dragonflies.

- Plant native grasses around the edge, interspersed with rock piles, to shelter toadlets.

- Never remove tadpoles from the wild to stock your pond. Only tadpoles that would otherwise perish because they're stranded in places like swimming pool covers should be relocated.

- Freshen pond water during dry spells or if it turns stagnant.

Copyright Notice

© Canadian Wildlife Federation

All rights reserved. Web site content may be electronically copied or printed for classroom, personal and non-commercial use. All other users must receive written permission.