Migration corridors are narrow ribbons of land or water that bridge the gap between isolated habitats. Examples include river valleys that serve as flyways for migratory birds and hedgerows that squirrels and deer mice use to scoot between woodlots. Urban and rural, large and small, these lifelines enable wide-ranging animals to find the food, water, shelter, and space they need to survive. As human developments continue to dice, mince, and pulverize natural areas, the need for connectivity between fragmented habitats becomes more vital.

To achieve that goal in your area, give the following projects a try.

Grow a Greenway

The jungly borders sometimes found around schoolyards, parks, houses, shopping malls, industries, and farms are herbaceous highways for animal migrants. Known as windbreaks, hedgerows, and shelterbelts, these wooded corridors — or greenways — are simply gigantic hedges. They consist of trees and shrubs, planted at least three rows wide, stretched out in long, thin lines that link woodlots, wetlands, and other key habitats. Not only do greenways serve as safe passages for species like weasels, rabbits, and voles, they also supply an abundance of food and spaces where everything from chipmunks to chickadees can rest, nest, and hide. Greenways baffle winds, too, protecting schoolyards from wintry drafts, providing shade for wildlife and people, and preventing soil from drying out and blowing away.

- Choose a site for your greenway, keeping in mind its primary purpose — to connect other habitats, such as thickets and marshes. Consider enhancing an existing hedgerow or other wooded corridor by planting supplemental trees and shrubs.

- Map your project site. Indicate the border where the greenway will stand. It should be at least three metres wide when fully grown. Include in your map features like buildings, roads, and habitats that will be linked.

- Consult with regional departments of wildlife, forestry, and agriculture for advice on your plan and your choice of native trees and shrubs.

- Space plants so they'll have enough room to grow: 50 or 60 centimetres apart for shrubs, twice as far apart for trees.

- Throw neatness to the winds. Plant your greenway in gently zigzagging rows — the tallest trees in the middle rows, the shortest shrubs along the outside — with deep recesses where wildlife can hide. Arrange the trees or shrubs in each row so they alternate with those in neighbouring rows.

- Ideal trees for middle rows are white spruce, red ash, white cedar, and Manitoba maple. Include both coniferous and deciduous species for a wide variety of food and shelter. Blackberry, raspberry, elderberry, hawthorn, and buffaloberry are suitable shrubs for outer rows.

- Water the plants regularly until they're well established.

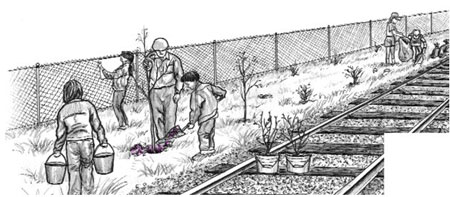

Turn Rails into Trails

Once key transportation for cargo and passengers, trains are fast losing ground to cars, trucks, and planes. We have abandoned thousands of kilometres of railroad in Canada in recent decades. The good news is that these empty corridors, whether in timberlands or concrete jungles, provide precious pathways for wildlife — and for hikers, bird-watchers, and cross-country skiers. Chances are a deserted railway corridor runs through your community. If so, why not turn those empty rails into wildlife trails?

- First, make sure the railway is actually abandoned. The sudden arrival of a nightly express could ruin any planting party.

- Ask your municipality for permission to adopt a stretch of the corridor as a greenway for wildlife. Seek advice from local conservation authorities.

- Collect any garbage left at the site. Post signs discouraging dumping and informing passers- by of your project goals.

- Enhance the area for pollinators by planting wildflowers attractive to butterflies, bees, and hummingbirds (see "Nurture a Nature Corridor", below).

- For maximum wildlife benefits, plant native berry-producing shrubs, such as hawthorn, blackberry, and elderberry, along the tracks, leaving a travelling lane down the middle. If the corridor is fenced, plant climbing vines, such as honeysuckle, grapevine, and bittersweet, along the edge. These plants will give wild tenants and travellers a much-needed boost with their fruits and blooms.

Restore a Riparian Corridor

Waterways and the lush vegetation along them are natural paths for migrants travelling by air, land, and water. Abounding with food, water, shelter, and space, these riparian zones help creatures make their way through increasingly fragmented landscapes of urban and rural development. Learn how to conserve these “ribbons of life.”

Nurture a Nectar Corridor

The next hummingbird or butterfly that hovers your way could be following a "nectar corridor." Certain species migrate over paths that stretch thousands of kilometres in length while pursuing plants that bloom sequentially — north to south in fall, south to north in spring. These pollinating pilgrims need nectar to fuel their long-distance flights. In exchange, they unknowingly transfer pollen from bloom to bloom. This process, known as cross-fertilization, ensures the reproduction and genetic mixing of wild plants and cultivated crops.

Today, this essential service is threatened by pollution and pesticides as well as by habitat fragmentation resulting from land developments like industries, parking lots, and shopping malls. Many nectar corridors are no longer intact. Travellers must "island hop" across scattered habitats that contain little food. This lack of fuel is much to blame for dramatically decreasing populations among migratory pollinators. At stake is their future and the critical role played by pollination in sustaining natural communities and in putting food on our plates.

It's time we rose to the challenge of nurturing nectar corridors back to health. Here's how you can help:

- Spread the word about the inestimable value of pollinators. Use posters, stories, poems, speeches, and other media to make a statement.

- Find out if there's an important pollinator stopover in your area. Seek advice from an entomologist at a local university or your regional natural resources ministry.

- If the site is at risk, consider habitat enhancement strategies, such as the pollinator projects below.

- Adopt the migratory stopover and ask your community to declare it a pollinator preserve.

- Work with other communities along the same corridor. Share information, discuss conservation concerns, and collaborate on pollinator projects.

- Purge pesticides from your municipality. See page “Purge Pesticides from Your Schoolyard and Community” for suggestions on how to persuade your town council to impose a ban on bug and weed killers.

- Keep watch over migratory pollinators, including red admirals, painted ladies, and monarch butterflies, by participating in a butterfly survey.

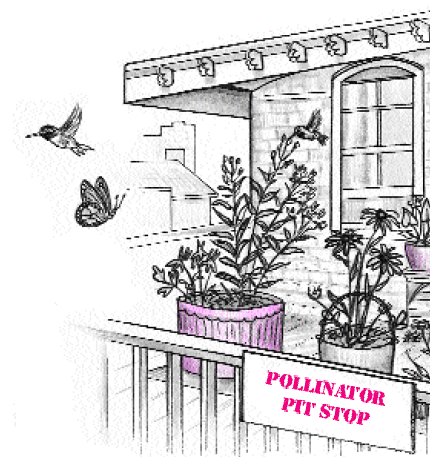

Provide Pollinator Pit Stops

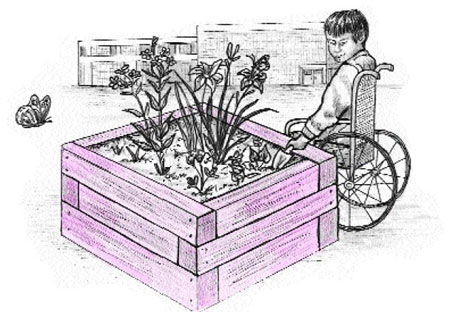

Invite pollinators into a courtyard or other parts of your school grounds where once the bravest butterflies dared not go. Make the invitation irresistible by growing wildflowers laden with nectar and pollen in containers of all kinds. The perfect project for inner city schools with scarce land and funds, container gardening provides wildlife habitat that is both productive and portable — a moveable feast.

- Collect an array of planting containers. Use commercial ones made of wood, metal, plastic, clay, and ceramic or recycled ones supplied by students. Anything that holds soil and is large enough to allow healthy plant growth — tin cans, milk pails, old buckets, feeding troughs, waste-paper baskets, wheelbarrows, rusty wagons, enamel basins, half whisky barrels, orange crates lined with plastic, flue tiles or drain pipes standing on end — will do beautifully.

- Poke or drill drainage holes in container bottoms. Add a layer of pebbles to encourage seepage. Fill pots with moisture-retaining soil.

- Select an array of native annual blooms to attract an array of pollinators (see "Pollinator Plants" below). Perennials must be planted in the ground or brought indoors to survive the winter.

- Place containers in sunny, preferably sheltered, parts of your courtyard. Arrange them on surfaces, such as planks laid across cement blocks and multi-level shelves or "terraces" made of plastic-coated metal. Nestle larger receptacles in corners. Hang planters from arbours, fences, railings, arches, and walls. Use lattices and trellises to support vines planted in pots on the ground.

- Water plants regularly, especially those in smaller containers, until they're established.

- For broader benefits to your nectar corridor, students could take these easily maintained projects home to their own backyards and balconies for the summer.

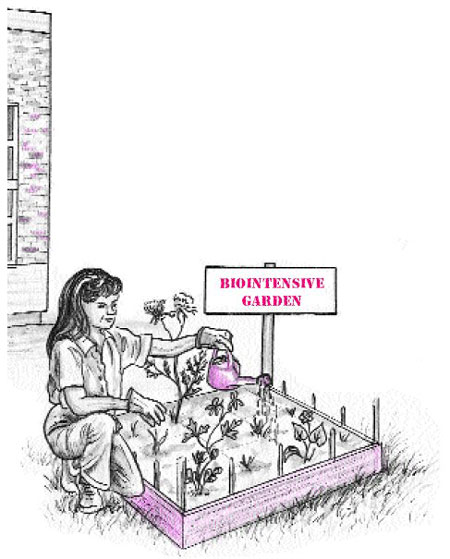

The amount of land at your command may seem too puny to make a difference in the grand scheme of things. But even a bounteously blooming square yard (or a square metre) could constitute a small but significant part of a nectar corridor. That's where "biointensive gardening" — the practice of growing closely spaced wild plants in miniature plots — comes in.

- Select a well-drained spot that receives six to eight hours of sunshine a day. Both sides of the entrance to your school, a private home, or seniors' residence are ideal locations.

- Think small. Just one or two square-metre gardens could meet your objectives.

- Circumscribe your plot with string, bricks, or preferably lumber. A raised bed enclosed in four-by-four landscaping timber (untreated) offers several advantages: protection from foot traffic, better drainage, deeper topsoil, and easier accessibility.

- Till the soil to a depth of at least 30 centimetres. Then mix in one part compost or well-aged manure to two parts existing soil.

- Divide the plot into 16 squares with string. Each square will hold a different species of wildflower (see "Pollinator Plants", below).

- Plant several seedlings or pinches of seeds in each square, in closely spaced, slightly staggered rows.

- Water the plot regularly, especially during dry weather.

Pollinator Plants

- Hummingbirds and swallowtail butterflies favour red flowers with bell, tube, and trumpet shapes. Fireweed, columbine, salvia, day-lily, trumpet honeysuckle, cardinal-flower, delphinium, blazing-star, phlox, and wild geranium are some of their favourites.

- The best nectar choices for adult butterflies are dogbane, asters, milkweed, goldenrod, fleabane, thistle, peony, lupine, vetch, and phlox.

- Good sources of nourishment for butterfly caterpillars include sedum, violet, clover, black-eyed Susan, and Queen Anne's-lace.

- Monarch butterfly caterpillars eat only milkweed. Widely regarded as a noxious plant, common milkweed has several close relatives — including butterfly-weed, red milkweed, and swamp milkweed — all of which are good hosts to monarch larvae. Ask a bylaws officer if these plants can be grown in your area.

Copyright Notice

© Canadian Wildlife Federation

All rights reserved. Web site content may be electronically copied or printed for classroom, personal and non-commercial use. All other users must receive written permission.