Dammed Inconvenient

Many of Canada’s lakes, streams and rivers are part of ancient migratory routes that have been travelled by aquatic species for thousands of years. At various stages of life, salmon, sturgeon, American Eel and many other species have evolved to use different parts of these systems to hatch, mature and breed.

Over time, the construction of road culverts, dams and other structures has created barriers to fish swimming these ancient routes. In many places, fish can no longer pass from one important habitat to another. This loss of passage has been a major factor in the decline and disappearance of many species.

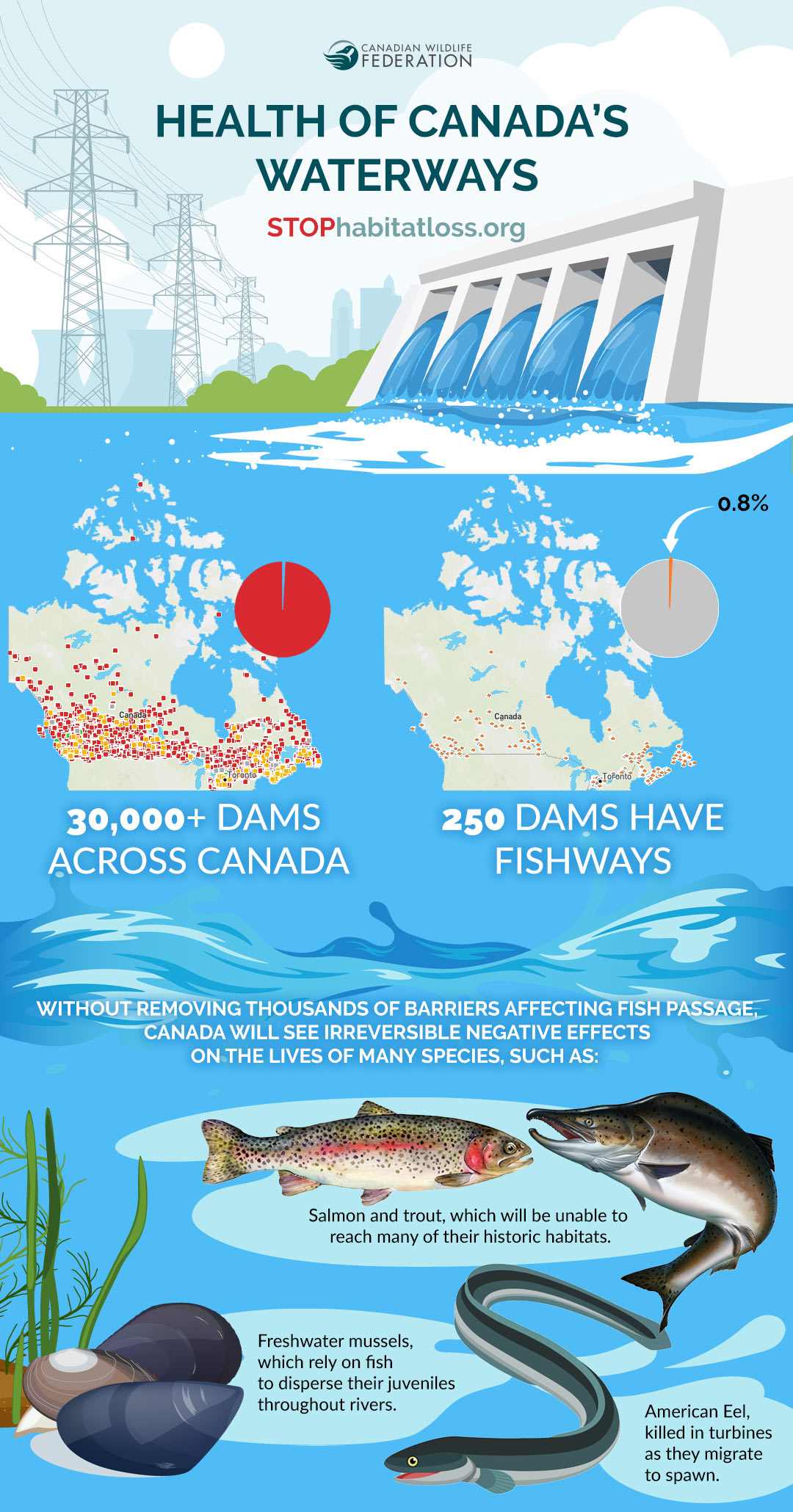

The Canadian Wildlife Federation is actively tracking and mapping aquatic barriers through the Canadian Aquatic Barriers Database (CABD). What we’ve learned so far tells a damming story about the health of Canada’s waterways. For example, while there are over 30,000 dams across Canada, only 250 are currently known to have fishways that provide upstream passage for aquatic species. While some rivers and streams have many kilometres of unobstructed flow, others have so many barriers they are simply unavailable to many species.

The good news is that many of these aquatic barriers can be fixed or decommissioned. Other measures can be taken to ensure safe passage around them. The United States is meeting this challenge head on by funding and implementing programs that have seen 800 dams removed in the past 10 years. Similarly, within the European Union in 2022 there were 325 river barriers removed, including several hydro-electric dams. Closer to home, in British Columbia, CWF is working with multiple partners to restore hundreds of kilometres of fish passage throughout the province. In the past five years, this work has restored access to more than 3.3 million square metres of habitat (328 hectares) at 25 sites throughout British Columbia.

On a national scale, however, Canada has fallen behind. A lack of federal funding and coordination on this issue means further endangerment of our nation’s freshwater species.

There are hundreds of thousands of human-made barriers in Canada’s rivers and streams that limit the movement of fish and other aquatic animals, many of which rely on annual migrations to complete their life cycle. This loss of access to important habitat is one of the reasons fish populations are in decline across the country.

One example is Canada’s salmon populations, which are at an all-time low with many facing imminent risk of extinction.

The bright side of this story is that the habitat above a barrier is often still in excellent condition and all that is needed is to reconnect the river by eliminating the barrier. We call this restoring fish passage. An added benefit is that restoring access to habitat will help fish adapt to a changing climate and make important infrastructure like roads and railways more resilient to flooding.

This is why the Canadian Wildlife Federation is committed to reconnecting our rivers and streams to stop habitat loss. Other countries have already recognized the benefits and acted. The United States has committed over $2 billion to upgrade infrastructure to restore fish passage.

Without removing thousands of barriers affecting fish passage, Canada will see irreversible negative effects on the lives of many species like:

- Salmon and trout that are unable to reach many of their historic habitats

- American Eel, which are killed in turbines as they migrate to spawn

- Freshwater mussels, which rely on fish to disperse their juveniles throughout rivers

For the sake of our fish, other affected species, and their habitat, we are asking the Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada to establish a National Fish Passage Program aimed at reconnecting our rivers and streams as part of Canada’s commitment to achieving the 2030 Global Biodiversity Targets.

Challenges and Solutions

Why Is This Issue So Concerning?

Across Canada, many small projects and construction activities occur in and around rivers, lakes and streams every day. These include dredging, excavation, the installation of water intakes, shoreline hardening, and the installation of dikes, culverts, and water crossings. Many of these small projects have an impact on water quality and habitat. Here are some examples.

Gaps in the Fisheries Act

The federal Fisheries Act prohibits direct harm, destruction or alteration of fish habitat, and the death of fish by means other than fishing. It requires that owners of barriers that are harming fish and fish habitat report these harms to the Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) and correct them. The Act gives DFO the power to order any obstruction to fish passage either removed or modified to allow passage. Unfortunately, such requirements are rarely enforced, and these powers are rarely exercised by DFO. This needs to change.

Compliance with the Fisheries Act should be required when it comes to the harm caused by aquatic barriers. It should be implemented to hold past owners of aquatic barriers accountable for both mitigation or removal, and for restoration of fish habitat at the end of the structure’s life. The Act should be revised to ensure future projects don’t obstruct fish passage, unless they are granted special permission from DFO that is accompanied by plans to mitigate and offset harm to fish and their habitat. This should be accompanied by transparent enforcement and compliance efforts.

As a concrete objective, CWF recommends that the existing Fisheries Act be applied to require passage at 2,500 structures currently blocking fish migration. This commitment would pull Canada in line with the international community making similar conservation commitments.

Data Deficiencies

Though CWF has been working to document the extent of the aquatic barrier issue in Canada, it can be difficult to gain access to data and information about existing barriers. In some places, records are not publicly available, and in others, the barriers simply have not been mapped. Our work is on-going and requires continued relationship development and coordination with various organizations, governments and industry. Though there is already a staggering number of barriers identified in the Canadian Aquatic Barriers Database, we know this is an underestimate. CWF can’t do it alone – Canada needs a National Fish Passage Program that helps create an inventory of these barriers.

National Fish Passage Program

Canada needs a National Fish Passage Program that will coordinate efforts to identify, regulate, enforce and educate on aquatic barriers. The program should support the removal of dams and barriers that have exceeded their lifespan, support fish passage measures like fish lifts and bypasses, and support aquatic habitat restoration where fish habitat has been disturbed. We recommend the program be in place by 2026, supported by $200 million in funding, to help reconnect Canada's rivers and streams by restoring the fish passage at 1,000 barriers by 2030.

What Are Some Examples of Affected Species?

When added together, a series of small construction projects can have a big impact on fish such as trout, salmon, sturgeon, bass, and walleye. Turtles, amphibians, and water birds can also be affected. Here are examples of two species affected by the cumulative effect of small projects.

Spiny Softshell Turtle

Spiny Softshell turtles love the mud associated with many freshwater shorelines in Southern Ontario. They’ll often bury their uniquely flat bodies in the muck and use their long tubular noses as a snorkel. In early summer each year, female turtles seek sand or gravel sites to make their nests. But these days nesting sites are hard to find. Shoreline and riverbank stabilization projects have reduced softshell habitat. These projects happen everywhere, including urban areas where erosion mitigation measures prevent turtle access. These measures include concrete retaining walls, large boulder armoring (AKA rip rap) and gabion baskets. Not only does this kind of shore stabilization prevent turtle use in most cases, but it can cause unnatural water flows and change sediment dispersal potentially further altering habitat. Bank armoring and other threats have landed the softshells on the federal endangered species list. But it doesn’t have to be this way. There are alternative shore stabilization techniques that are turtle friendly.

Coho Salmon

From the time a Coho Salmon fry hatches from its egg to its return to the same freshwater system to spawn, they are on the move. They wind their way through hundreds of kilometers of streams and rivers as they navigate to the ocean and back a few years later. When in their freshwater habitat, Coho Salmon prefer very small, low gradient streams. These streams are vital to their health and survival and have many benefits. Coho grow faster in smaller tributaries and side channels compared to those that use main-stem river channels. In broad floodplains with many of these small channels, the Coho smolts (juveniles transitioning to saltwater habitat) are larger. Unfortunately, small projects and habitat alterations are common in these streams. In the agricultural area of the Fraser Delta, BC, channel dredging to remove instream and shoreline vegetation is common.

What YOU Can Do

Support our efforts with a donation

The Canadian Wildlife Federation’s petition brings awareness to government, industry and all Canadians about the many threats facing Canadian aquatic habitat and the species that rely on it. Consider supporting CWF and our work on the Canadian Aquatic Barrier Database — donate now to ensure this essential work continues.

Spread the Word

The Canadian Wildlife Federation’s petition brings awareness to government, industry and all Canadians about the many threats facing Canadian aquatic habitat and the species that rely on it. Consider supporting CWF and our work on the Canadian Aquatic Barrier Database — donate now to ensure this essential work continues.